شبیهسازی دستگاه ناحیه بزرگ – بخش C: ویرایش هندسه کنتاکت (شکل و اندازه)

در بخش B، هندسه کنتاکت را ثابت در نظر گرفتیم و بررسی کردیم که افتهای مقاومتی چگونه به ویژگیهای مواد و تنظیمات اسکن وابسته هستند. با این حال، در عمل قدرتمندترین پارامتر در اختیار شما هندسه است: الگوی مش، گام آن، عرض خطوط آن و اندازه دستگاهی که باید آن را پوشش دهد.

در این بخش ساختار فیزیکی کنتاکت را تغییر خواهیم داد. این کار شامل جابهجایی بین الگوهای مختلف لانهزنبوری، ویرایش ابعاد مش زیرساختی و تغییر اندازه زیرلایه شبیهسازیشده است.

💡 نکته: اگر میخواهید الگوهای مش خود را از تصاویر دوبعدی تولید کنید (برای مثال از یک ماسک چاپی، تصویر میکروسکوپی یا خروجی CAD)، به /manual/tutorial-shape-db-part-a.html مراجعه کنید. این همان روشی است که برای پر کردن Shape Database مورد اشاره در ادامه استفاده میشود.

مرحله 1: باز کردن Object Editor برای مش فلزی

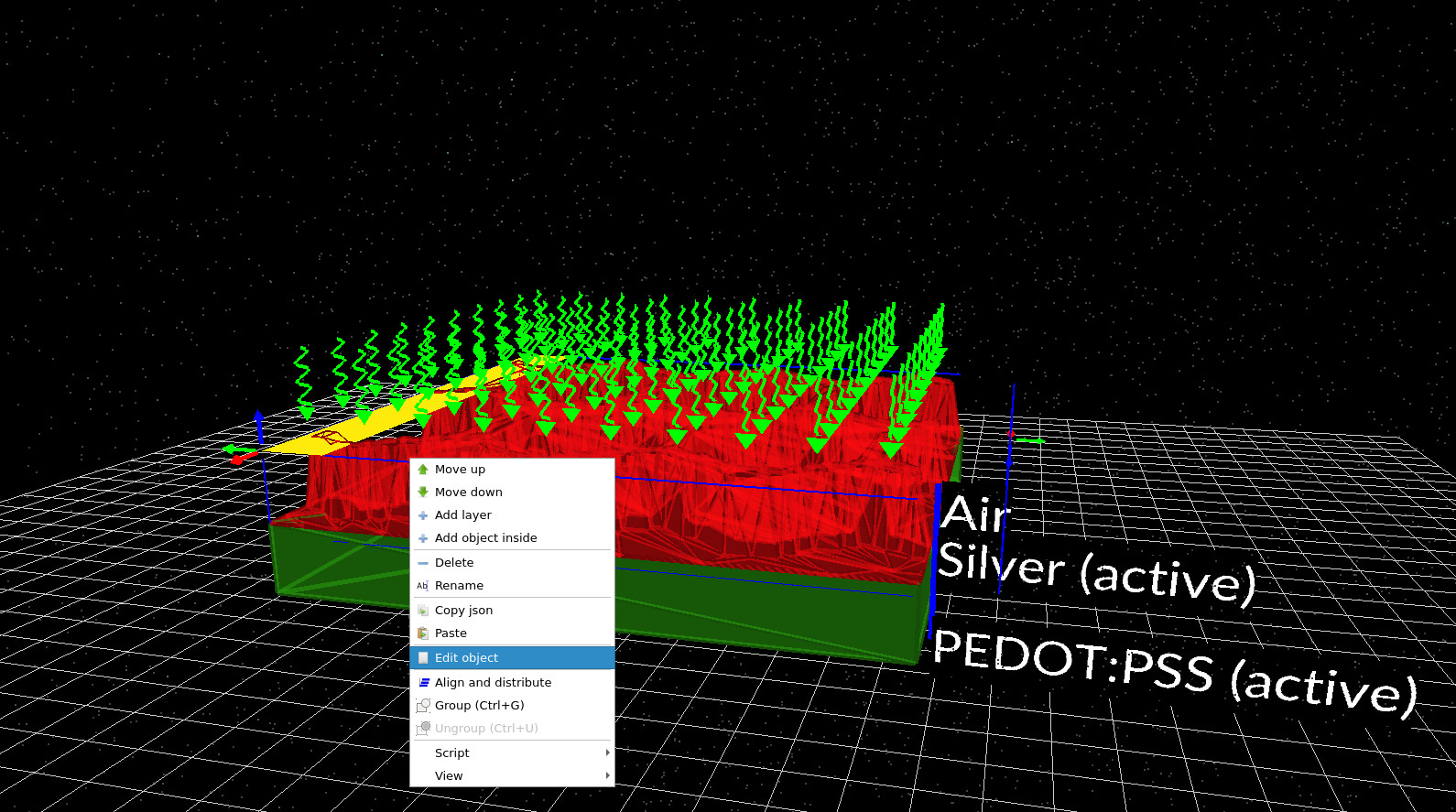

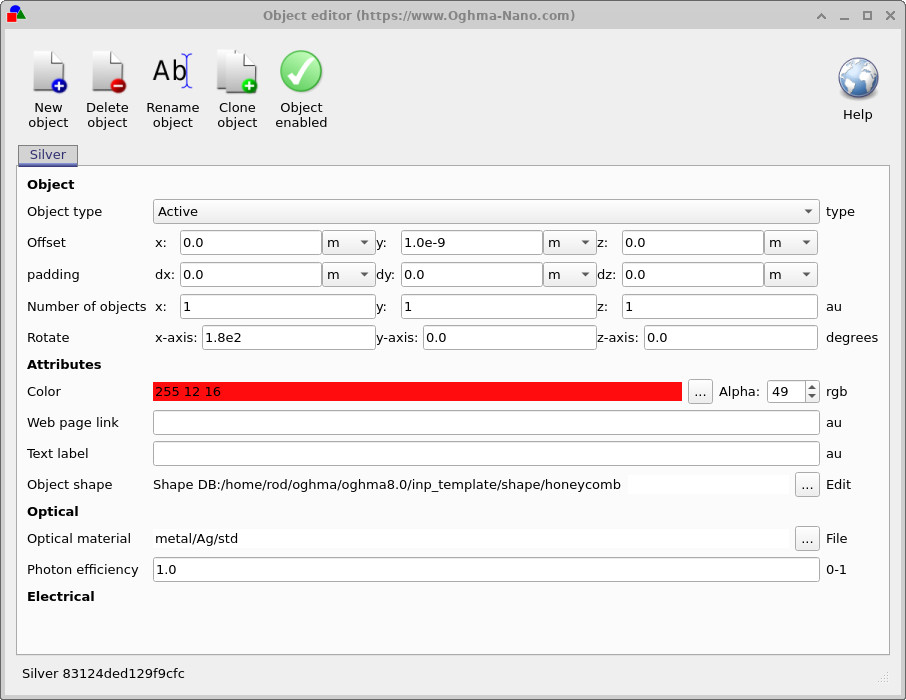

در نمای سهبعدی، روی مش فلزی ششضلعی راستکلیک کرده و گزینه Edit object را انتخاب کنید (به ?? مراجعه کنید). این کار Object Editor را باز میکند (??).

این ویرایشگر تقریباً تمام جنبههای شیء را قابل تغییر میکند. با این حال توجه داشته باشید که این مش درون یک ساختار اپیتاکسی لایهای قرار دارد و در فضای آزاد نیست، بنابراین برخی گزینهها بهطور طبیعی توسط پشته لایهها محدود میشوند.

- Attributes: تغییر رنگ (و آلفا) برای وضوح بیشتر در نمایش.

- Optical material: جایگزینی تعریف ماده (مفید در صورت ترکیب شبیهسازیهای الکتریکی و نوری).

- Object shape: انتخاب الگوی هندسی مورد استفاده برای ساخت مش (این مهمترین کنترل برای عملکرد الکتریکی است).

مرحله 2: تغییر الگوی لانهزنبوری از طریق Mesh Editor

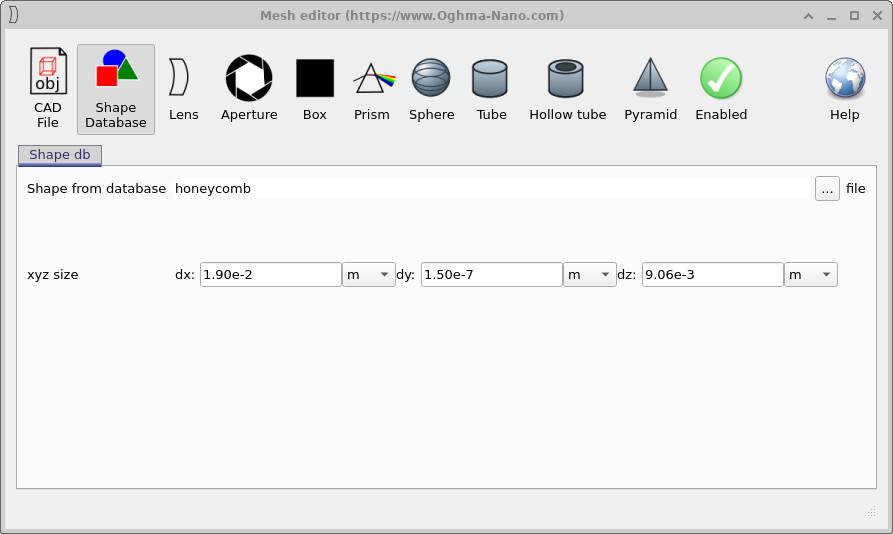

در Object Editor، گزینه Object shape را پیدا کنید. در حال حاضر مش از Shape Database فراخوانی میشود (برای مثال honeycomb). روی سه نقطه کنار Edit کلیک کنید تا Mesh Editor باز شود (به ?? مراجعه کنید).

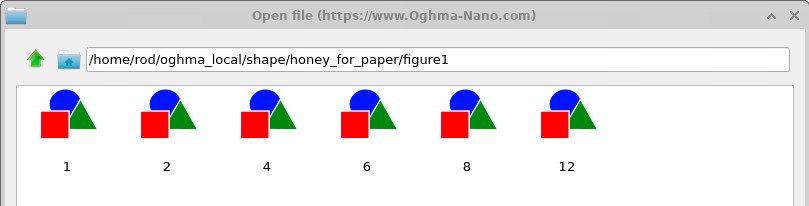

در Mesh Editor، روی سه نقطه سمت راست گزینه Shape from database کلیک کنید. این کار مرورگر Shape Database را باز میکند (به ?? مراجعه کنید). در این مثال به پوشهای شامل چندین نوع الگوی لانهزنبوری (که قبلاً برای شکلهای یک مقاله استفاده شدهاند) میرویم و یکی را انتخاب میکنیم.

همه اشکال برای کنتاکتها از نظر فیزیکی مناسب نیستند. یک مش کنتاکت باید یک شبکه رسانای پیوسته تشکیل دهد که بهطور معقول با پلیمر زیرین در تماس باشد. اشکال تزئینی یا آزاد (برای مثال gaussian یا teapot) معمولاً ساختار جمعآوری جریان معتبری تشکیل نمیدهند. الگوهای لانهزنبوری نقطه شروع طبیعی هستند زیرا شبکهای پیوسته با سلولهای تکرارشونده ایجاد میکنند.

اگر میخواهید الگوهای خود را ایجاد کنید (برای مثال از تصویر یک ماسک چاپی)، روند توضیح داده شده در /manual/tutorial-shape-db-part-a.html را دنبال کرده و سپس آنها را به Shape Database وارد کنید.

مرحله 3: تغییر اندازه دستگاه

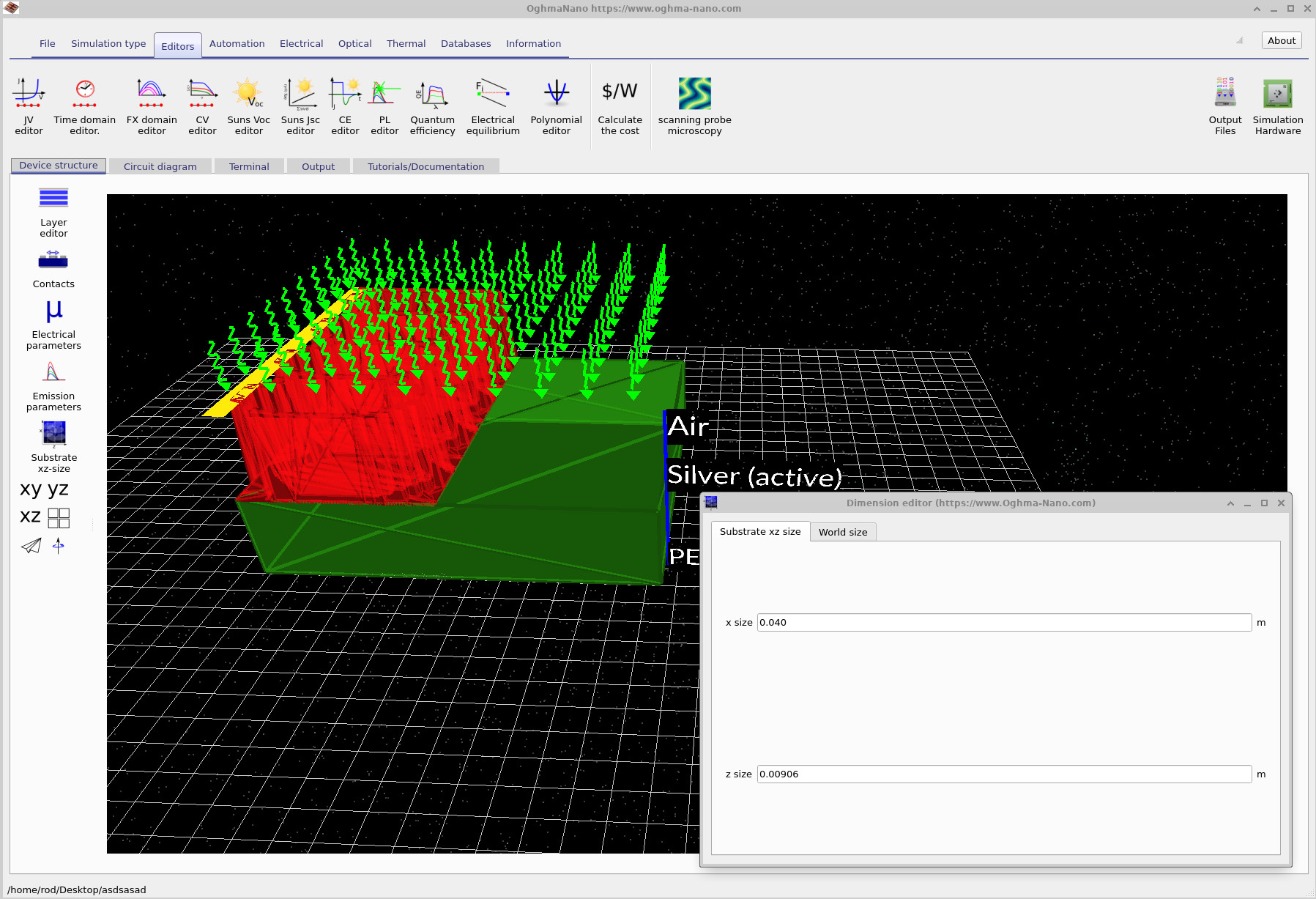

میتوانید اندازه کلی دستگاه را با کلیک روی Substrate xz-size در نوار سمت چپ پنجره اصلی تغییر دهید. این کار ویرایشگر ابعاد نشان داده شده در ?? را باز میکند.

در مثال بالا اندازه زیرلایه دو برابر شده است. بلافاصله نکته مهمی را مشاهده خواهید کرد: زیرلایه بزرگتر میشود اما مش لانهزنبوری بهطور خودکار آن را دنبال نمیکند. این به این دلیل است که مش یک شیء سهبعدی است که ابعاد مطلق آن در Mesh Editor تعیین میشود (به ?? مراجعه کنید)، نه توسط کنترل اندازه زیرلایه.

بنابراین تغییر اندازه دستگاه یک عملیات دو مرحلهای است:

- تغییر اندازه substrate (اندازه جهان/دستگاه).

- تغییر اندازه mesh object در Mesh Editor تا کل زیرلایه جدید را پوشش دهد.

نتیجهگیری: یک گردشکار عمومی برای مسائل پیچیده کنتاکت سهبعدی

اکنون یک گردشکار کامل برای شبیهسازی کنتاکتهای شفاف/فلزی ناحیه بزرگ دیدهاید:

- ساخت یک پشته کنتاکت لایهای (پلیمر + مش فلزی + کنتاکت استخراج).

- اجرای حل اسکن برای ترسیم نقشه مقاومت مؤثر و افت ولتاژ در سراسر دستگاه.

- تغییر هندسه (الگوی مش، اندازه، گام) و اجرای مجدد برای کمیسازی بهبودها.

این روش محدود به سلولهای خورشیدی نیست. هر دستگاهی که در آن جریان باید بهصورت جانبی از طریق یک لایه مقاومتی گسترش یابد—پنلهای OLED، مواد الکتروکرومیک، حسگرها، الکترونیک انعطافپذیر، آشکارسازهای نوری ناحیه بزرگ—میتواند به همین روش تحلیل شود. نکته کلیدی این است که فیزیک مسئله تحت سلطه جمعآوری جریان مقاومتی است و بنابراین نمایش مدار سهبعدی هم مناسب و هم از نظر محاسباتی کارآمد است.

👉 گام بعدی: این گردشکار را روی الگوهای کنتاکت خود اعمال کنید؛ با وارد کردن اشکال در Shape Database و تنظیم مقاومتها مطابق با مواد اندازهگیریشده خود.